When Memory Fades, the Clock Starts: A Vermont Family’s Guide to Early Dementia Planning

If you’re wondering when to contact an attorney because you’ve noticed a loved one struggling with their memory, the answer is right now.

In Vermont, we value independence and “figuring it out.” However, the law is clear: an individual can only sign essential legal documents if they have the “legal capacity” to do so. Waiting even a few months can turn a simple afternoon of paperwork into a complicated, public, and expensive court process.

Conditions like Dementia and Alzheimer’s are progressive; the window for your loved one to make their own choices can close unexpectedly.

The High Cost of Waiting

In Vermont, the financial stakes are high. As of January 2026, the average cost for a private room in a Vermont nursing home has reached approximately $16,303 per month ($195,640 annually). Even assisted living facilities average over $8,352 per month in the state.

These costs can extinguish a lifetime of savings in a matter of months. Proper planning allows you to explore Medicaid eligibility and asset protection strategies that are simply not available once capacity is lost.

Understanding "Capacity" in Vermont

The legal definition of capacity is not a single "on/off" switch. In Vermont, attorneys use a task-specific standard known as Testamentary Capacity. This is a lower legal threshold than the capacity required to enter into a contract. Even if a loved one has a medical diagnosis of dementia but still has “lucid intervals,” they may still be legally "clear" enough to sign documents.

To determine if a person has a "sound mind" to sign a Will, Vermont attorneys assess four specific factors:

Nature of the Act: Does the person understand they are making a will to distribute their property?

Natural Objects of Bounty: Do they know who their closest family members and heirs are?

Extent of Property: Do they have a general idea of what they own (e.g., "I own my house and my savings account")?

Rational Plan: Can they hold these three thoughts in their mind at once to create a logical plan for their estate?

The standard differs based on the document. For example, for a Power of Attorney they must understand that they are giving another person the power to act in their place.

Note: An attorney makes this judgment on-site. It is a "judgment call" based on open-ended interviewing. If a loved one is having a "bad day," it is standard practice to reschedule for a time when they are more alert.

Essential Documents for Your Loved One

Every adult, particularly those showing early signs of cognitive decline, should have these four documents:

Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA): Names an "agent" to handle finances. The word "Durable" is vital—it means the power remains in effect even if the person becomes incapacitated. Once granted, the agent can access the grantor's accounts, pay their bills, etc.

Advance Directive for Health Care: Allows your loved one to choose a healthcare agent to make medical decisions and outlines wishes for palliative care and end-of-life treatment. This gives them a voice if they can’t speak for themselves.

Will: Assigns an executor and dictates how assets are distributed. Without this, the state of Vermont decides who gets what via "intestacy" laws.

HIPAA Release: Explicitly authorizes doctors to share medical information with those listed. Without this, privacy laws can lock family members out of the loop during a crisis.

Protecting Assets from Medicaid

A common misconception is that you must be "broke" to qualify for Medicaid. While there are strict asset limits, Vermont law allows for certain protections for a primary residence and a spouse living at home.

However, Medicaid has a five-year look-back provision. This means Medicaid reviews any gifts or property transfers made in the five years before you apply. Any such transfer can trigger a "penalty period" where Medicaid refuses to pay. Acting early is the best way to ensure your loved one gets the care they need without leaving the family with nothing.

When Planning is Left Too Late: Guardianship

If a loved one’s memory has declined to the point where they can no longer meet the capacity standards mentioned above, your only option may be Guardianship.

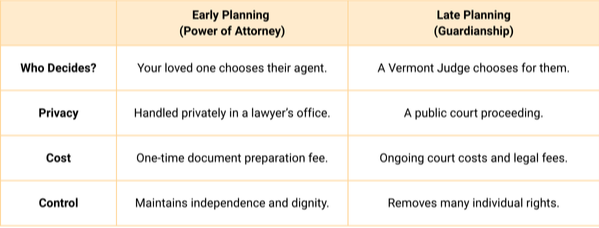

This is a formal court process where a judge will decide who will manage the person’s affairs. It is more expensive, public, and time-consuming than a Power of Attorney, which is why early planning is so strongly encouraged.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, that’s okay. There’s a lot to consider and digest. Take this one step at a time. The first piece of the puzzle is a confidential conversation to see where things stand. Schedule an initial consultation with an experienced estate and Medicaid planning attorney today.